Citizen Science in Environment Agency’s eutrophication assessments

The Environment Agency is using citizen science data to make a measurable difference to how the Environment Agency Eutrophication Assessment Weight of Evidence Tool works in practice: improving confidence, refining local priorities, and helping regulators, industry, Rivers Trusts and CaBA partners focus efforts where they matter most. Here we show how it made a difference in the Ribble.

Bringing citizen science into the evidence base

The Environment Agency’s Eutrophication Assessment Weight of Evidence (WoE) Tool is a decision support tool used by the Environment Agency to assess where rivers are suffering from eutrophication and to guide where further evidence or action is needed.

Through a collaboration between the Environment Agency and CaSTCo, partners have illustrated that citizen science data can potentially make a measurable difference to how this tool works in practice: improving confidence, refining local priorities, and helping regulators and communities focus efforts where they matter most.

This case study explores how the approach worked in practice in the Ribble catchment, what changed when citizen evidence was added, and the huge potential for scaling this collaboration. It also sets out key recommendations for how the next version of the tool could routinely include citizen science data.

The problem: nutrient pressures on rivers

Eutrophication is the enrichment of a water body with nutrients, primarily phosphorus and nitrogen, leading to excessive plant and algal growth. It remains one of the main pressures on river health. While wastewater treatment and agriculture are both major sources, their relative impacts vary between catchments, and many rivers continue to face complex, combined pressures where the causes aren’t obvious.

The Environment Agency’s Eutrophication Assessment Weight of Evidence (WoE) Tool brings together data on phosphorus, plants and algae with local evidence to judge where eutrophication is happening. But many waterbodies still sit in the “uncertain” category, where there isn’t enough data to be sure.

At the same time, citizen scientists are already collecting evidence that could fill those gaps. This case study shows how including their data can make national decisions clearer and more confident.

Who

This work was led through the Catchment Systems Thinking Cooperative (CaSTCo) partnership, bringing together expertise from across the national network.

- Environment Agency: developed and maintains the Eutrophication Assessment Weight of Evidence Tool, and is working with CaSTCo partners to support the inclusion of citizen science evidence within it in the future.

- The Rivers Trust: coordinated the national collaboration and helped align data and methods between partners.

- Ribble Rivers Trust: led the on-the-ground pilot in the Ribble catchment, integrating volunteer and staff monitoring data into the assessment.

- Citizen scientists and local volunteers: collected nutrient, algal, and observational data that filled key gaps and improved the confidence of assessments.

Together, these groups tested how local evidence could feed into national decision-making, creating a model that can be replicated across other catchments.

Acknowledgments: We are indebted to the volunteers, volunteer coordinator and staff from the Ribble catchment and RRT who spent many hours collecting data about their rivers. Without their dedication and skill this interpretation would not have been possible.

Where

The Ribble Rivers Trust works in the Northwest. This tool is used throughout England.

Assessing eutrophication evidence

In assessing eutrophication we normally collect 3 strands of evidence:

- Pressure evidence: Elevated nutrient concentrations or loadings (phosphate, nitrate).

- Primary impact evidence: Direct ecological responses to nutrient pressure, such as increased filamentous algae or macrophyte growth, or shifts toward more nutrient-tolerant species.

- Secondary impact evidence: Indirect effects of nutrient enrichment, including large diurnal swings in dissolved oxygen (DO) or pH, subsequent impacts on fish or invertebrates, and effects on recreational activities (e.g., cancelled regattas or fishing matches).

International and national legislation and actions have been taken to reduce or minimise the impacts of eutrophication.

£75-115 million

Annual cost of eutrophication in England and Wales (property values, recreation, drinking water treatment, ecology, tourism), plus £55 million per year in policy response costs (2003 estimate)

66%

% reduction in phosphorus loads from sewage treatment works by 2020. Agriculture and rural land management are now the main reasons water bodies fail to achieve good phosphorus status (Phosphorus: challenges for the water environment EA (2022))

About ‘Weight of Evidence’ (WoE)

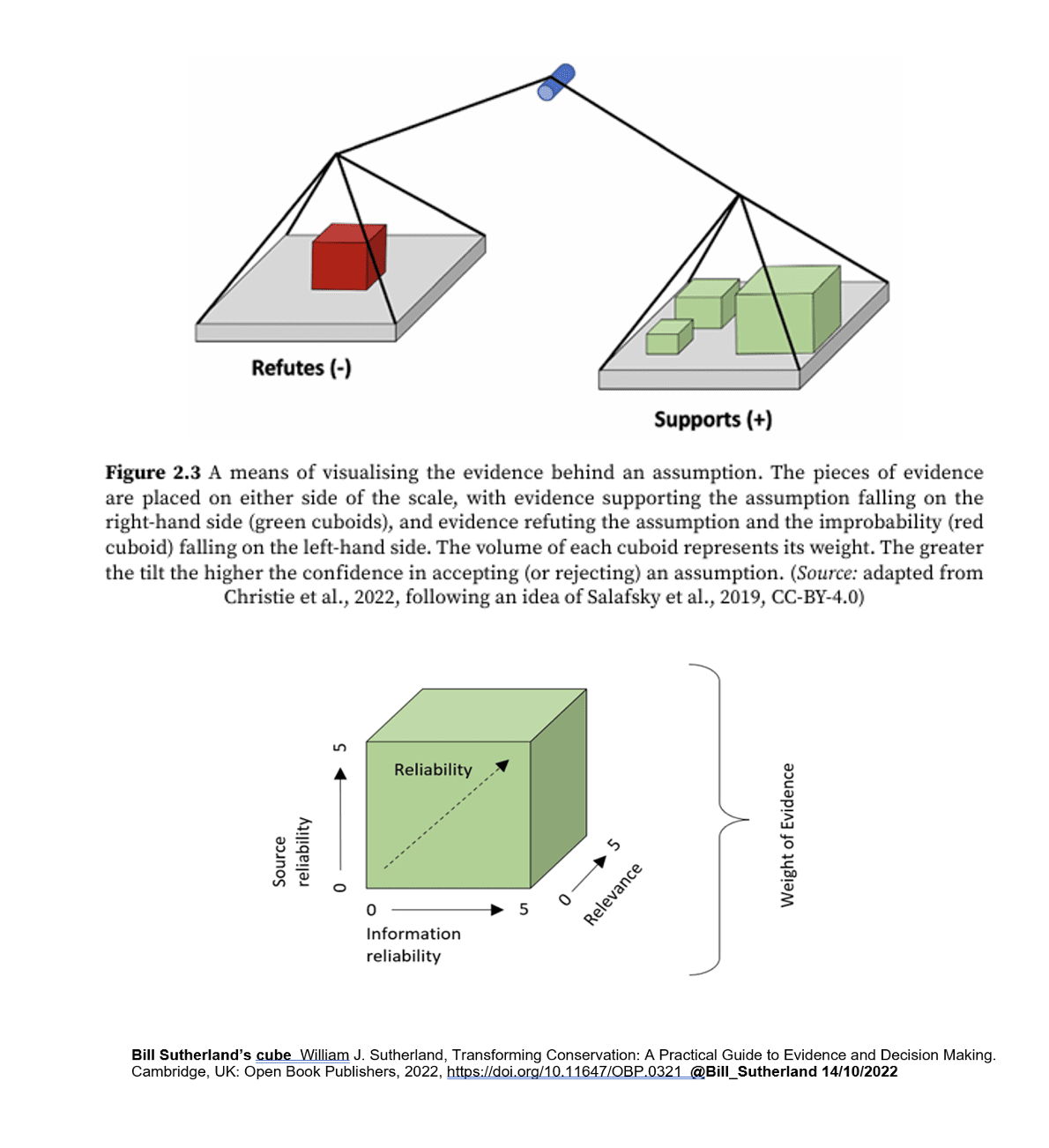

Evidence is ‘relevant information used to assess one or more assumptions related to a question of interest’. The Weight of Evidence approach (also referred to as Evidence Based Decision Making) is a key idea from CaSTCo. Learn more about Weight of Evidence here.

(modified from Salafsky et al., 2019)

Why we need a Weight of Evidence approach

Many environmental processes are highly complex with multiple impacts and pressures interacting with each other via a wide range of inter-related feedback loops and pathways that often make the observed impacts difficult to predict. Any particular piece of evidence usually shows only part of the overall picture. This is why we need multiple stands of evidence (the Weight of Evidence approach) to build an adequate understanding. Further evidence can either agree with or refute assumptions.

How the tool works

The Eutrophication Assessment Weight of Evidence (WoE) Tool combines national Water Framework Directive (WFD) data with local Environment Agency (EA) inputs to assess eutrophication risk and confidence. EA Areas use it to inform agricultural advice and water company investment through the Water Industry National Environment Programme (WINEP) and Asset Management Plan cycles (AMP). While the tool can include third-party evidence, such as citizen science data, but its use and weighting are currently inconsistent across EA Areas. Final risk decisions remain with EA experts.

The assessment process

Iterate: The process repeats in future assessment cycles, steadily improving understanding and confidence.

Initial assessment: EA runs the tool using national datasets on phosphorus, plants, and algae. The tool highlights where results are uncertain and suggests what extra evidence could help.

Add local evidence: Partners review what additional data exists, including staff monitoring, historic evidence, and now citizen science results, deciding what’s relevant or suitable to include.

Re-run the assessment: The tool is updated with this new evidence. Certainty levels may go up or down depending on what the data shows.

Review and act: Partners agree next steps: collect more data, investigate sources, or target interventions.

The impact: What changed in the Ribble

Adding citizen science and Ribble Rivers Trust data to the Eutrophication Assessment Weight of Evidence Tool made a measurable difference.

Across the Ribble catchment, data from volunteers and staff were available for 53 of 71 waterbodies. When entered into the tool, the results changed the classification for six waterbodies (11%): three became more certain that eutrophication is a problem, and three became less certain.

These changes improved confidence in the assessments and showed where further monitoring, investigation, or action could be better targeted.

Example 1:

Swanside Beck

Citizen scientists recorded phosphate levels of 0.18–0.20 mg/L as P at two upper-catchment sites using a low-range Hanna Checker.

This new evidence revealed localised nutrient pressures that weren’t previously captured, leading to an updated assessment:

From: “Uncertain eutrophication problem”

To: “Quite certain eutrophication problem”

This example shows how volunteer data can highlight localised nutrient issues invisible in national datasets. More details in the full analysis.

Example 2:

Upper Loud

Algal (RAPPER) surveys and phosphate samples collected by citizen scientists and Ribble Rivers Trust staff provided strong supporting evidence.

From: “Quite certain eutrophication problem”

To: “Very certain eutrophication problem”

Here, community evidence confirmed the scale of the issue and reduced uncertainty about eutrophication risk. More details in the full analysis.

Impact and implications

The Ribble pilot demonstrated that citizen science can directly improve national decision tools. By adding community and trust-collected data to the Eutrophication Assessment Weight of Evidence (WoE) Tool, assessments became more confident and better targeted.

This change has wider implications. It shows that:

- Citizen science can be used as credible evidence alongside environment agency monitoring.

- Collaborative monitoring between agencies, trusts, and volunteers can reduce uncertainty and guide smarter investment and target actions and advice.

- Decision tools can evolve from static datasets to living systems that continuously integrate new evidence.

The approach tested here provides a template for scaling across other catchments, and for applying the same logic to other environmental challenges beyond eutrophication.

Recommendations

The Ribble pilot proved that citizen science data can strengthen the Eutrophication Assessment Weight of Evidence (WoE) Tool), changing confidence levels in national assessments.

To build on this, the team identified a few practical steps to make community evidence part of every future assessment cycle.

1. Add citizen science evidence fields: Include new data categories in the tool so community and trust-collected evidence can be recognised and valued. This could cover:

- Nutrient samples (phosphate or nitrate)

- Algal or macrophyte surveys and photos

- Reports of sewage spills or CSOs

- Observations of impacts on recreation or aesthetics

2. Develop national guidance: Work with the Environment Agency’s national team to give clear direction on how and when citizen science data can be used, what quality assurance is needed, and how local evidence can reduce uncertainty in assessments.

3. Embed collaboration: Encourage use of citizen science data within Collaborative Monitoring Plans (CMPs), ensuring local evidence directly supports EA assessments and helps target advice, nature-based solutions, and investment.

4. Make it visible: Publish national eutrophication maps that combine EA and citizen science data, helping catchment partnerships see where data gaps exist and where joint monitoring could have the biggest impact.

Looking ahead

The Ribble pilot is more than a local success, it’s proof that community evidence can strengthen national decisions. By working together, water utilities, regulators, trusts, and citizen scientists have piloted and shown how volunteer data can sit confidently alongside statutory monitoring to build a more complete picture of river health – this is a goal of the Supporting Citizen Science project.

This work directly supports CaSTCo’s goals: developing shared frameworks, tools, and data systems that make community evidence trusted, comparable, and useful for everyone. It shows how catchment partnerships can move from collecting data to using it collaboratively for action, closing the gap between evidence and investment.

As the Eutrophication Assessment Weight of Evidence Tool evolves, these lessons will help make collaborative, decision-ready evidence the norm — not the exception. It’s a glimpse of the future CaSTCo is working toward: a connected monitoring network where every dataset, from every level, helps restore rivers.

“Citizen science water quality monitoring is wide ranging, across different scales and for different aims, from anecdotal and incidental records to longer term continuous monitoring; our view is that all information is useful to provide catchment intelligence. Our description of tiered data and the potential use of these data can be found in our Technical Advisory Framework and tiered ‘jigsaw puzzle’.

Our internal review of how citizen science is currently used by the Environment Agency includes:

- Providing certainty to complement our data- e.g. eutrophication weight of evidence.

- Providing additional catchment intelligence through increased local spatial and temporal data to complement our monitoring.

- Supporting investigations by providing additional information and highlighting incidents or early warning signs of pollution.”

Kelly Haynes, Environment Agency